Chapter 2-Your Business Idea: The Quest for Value

Cheshire Package Store

Source: Used with permission from Robert Brown.

Robert Brown has been the owner and operator of the Cheshire Package Store for 25 years. It is one of several liquor stores in this town of 25,000 people. Some of his competitors are smaller or approximately the same size, and one is significantly larger. Robert is very clear in his understanding of what gives his store a competitive edge. He believes his establishment provides the setting that makes a customer feel at home. “My feeling has always been that small businesses must have a feeling of comfort. If your customers do not feel that they can ask you questions about the product or if they feel that they are imposing on you, then they are not likely to return.”

Robert took every opportunity available to better understand his customers and provide them with value. One way his business does this is by developing a personal relationship with its customers. This may mean carefully looking at checks or credit cards, not for security reasons, but to identify customers by name. Robert points out that he always pays careful attention to what customers like and dislike; by doing so, they develop confidence in his suggestions. To foster this confidence, he and his family actively engage their customers in conversations. Customers, Robert, and the employees share stories, which is a key way to build better customer relationships. By listening to his customers, Robert can identify what they are looking for and assist him in knowing what new products he might offer.

In addition to this personalized level of service, the Cheshire Package Store also recognizes the importance of other factors. Robert talks about the importance of maintaining a well-lit store with spacious aisles, making it an inviting place in which to shop. He is careful about even minor details, such as assuring that there are open parking spaces near the entrance to his store. He recognizes that even walking short distances to or from the store might be a burden or deterrent for his customers. Robert’s store possesses a cutting-edge inventory software package designed specifically for liquor stores. It enables him to track inventory levels, which can provide estimates for future inventory levels of different products; however, he sees this as a guide only. As he puts it, “Your knowledge of your customers will be the key determinant for your success.”

Robert also strongly believes that the success of a small business depends on the owner being there. Stores have their own personality, in his view, and that personality is created by the owner. This personality imparted by the owner impacts all operational aspects of the business—“Your employees will pick up on what you expect, and they will know what your customers deserve.”

2.1 Defining the Customer’s Concept of Value

LEARNING OBJECTIVES

- Define customer value.

- Understand the five sources of perceived customer benefits.

- Understand the three sources of perceived costs.

Look beneath the surface; let not the several qualities of neither the thing, nor its worth escape thee.

Marcus Aurelius Antoninus

In the previous chapter, Peter Drucker and W. Edward Deming placed the customer at the center of their definitions of the purpose of a business. They used the customer as being at the core of that purpose rather than focusing on financial measures such as profit, return on investment (ROI), or shareholders’ wealth. Drucker’s logic was that if a business did not create a sufficient number of customers, there never would be a profit with the business. Deming argued that delighting customers would become the basis for them to consistently return, and loyalty would ensure that the business would have a higher probability of surviving in the long term. The clearest way of doing that is by focusing on providing your customers with a clear sense of value. This emphasis on value will produce economic benefits. Gale Consulting explains the notion of value this way, “If customers don’t get good value from you, they will shop around to find a better deal.”“Why Customer Satisfaction Fails,” Gale Consulting, accessed December 2, 2011, www.galeconsulting.com/index.php?option=com_content&view=article&id= 18&Itemid=23. A recent study put it this way, “These firms have been successful…by consistently creating superior customer value—and profiting handsomely from that customer value.”George Day and Christine Moorman, Strategy from the Outside In (New York: McGraw Hill, Kindle Edition, 2010), 104–10.

Strong evidence indicates that this focus on making the customer central to defining the business translates into economic success. It has been estimated that the cost of gaining a new customer over retaining a current customer is a multiple of five. The costs of regaining a dissatisfied customer over the cost of retaining a customer are ten times as much.Forler Massnick, The Customer Is CEO: How to Measure What Your Customers Want—and Make Sure They Get It (New York: Amacom, 1997), 76. So a key question for any business then becomes, “How does one then go about making the customer the center of one’s business?”

What Is Value?

It is essential to recognize that value is not just price. Value is a much richer concept. Fundamentally, the notion of customer value is fairly basic and relatively simple to understand; however, implementing this concept can prove to be tremendously challenging. It is a challenge because customer value is highly dynamic and can change for a variety of reasons, including the following: the business may change elements that are important to the customer value calculation, customers’ preferences and perceptions may change over time, and competitors may change what they offer to customers. One author states that the challenge is to “understand the ever changing customer needs and innovate to gratify those needs.”Sudhakar Balachandran, “The Customer Centricity Culture: Drivers for Sustainable Profit,” Course Management 21, no. 6 (2007): 12.

The simple version of the concept of customer value is that individuals evaluate the perceived benefits of some product or service and then compare that with their perceived cost of acquiring that product or service. If the benefits outweigh the cost, the product or the service is then seen as attractive (see Figure 2.1 “Perceived Cost versus Perceived Benefits”). This concept is often expressed as a straightforward equation that measures the difference between these two values:

customer value = perceived benefits − perceived cost.

Figure 2.1 Perceived Cost versus Perceived Benefits

Some researchers express this idea of customer value not as a difference but as a ratio of these two factors.M. Christopher, “From Brand Value to Customer Value,” Journal of Marketing Practice: Applied Marketing Science 2, no. 1 (1996): 55. Either way, it needs to be understood that customers do not evaluate these factors in isolation. They evaluate them with respect to their expectations and the competition.

Firms that provide greater customer value relative to their competitors should expect to see higher revenues and superior returns. Robert Buzzell and Bradley Gale, reporting on one finding in the Profit Impact through Marketing Strategy study, a massive research project involving 2,800 businesses, showed that firms with superior customer value outperform their competitors on ROI and market share gains.Robert D. Buzzell and Bradley T. Gale, The PIMS Principles—Linking Strategy to Performance (New York: Free Press, 1987), 106.

Given this importance, it is critical to understand what makes up the perceived benefits and the perceived costs in the eyes of the consumer. These critical issues have produced a considerable body of research. Some of the major themes in customer value are evolving, and there is no universal consensus or agreement on all aspects of defining these two components. First, there are approaches that provide richly detailed and academically flavored definitions; others provide simpler and more practical definitions. These latter definitions tend to be ones that are closer to the aforementioned equation approach, where customers evaluate the benefits they gain from the purchase versus what it costs them to purchase. However, one is still left with the issue of identifying the specific components of these benefits and costs. In looking at the benefits portion of the value equation, most researchers find that customer needs define the benefits component of value. But there still is no consensus as to what specific needs should be considered. Park, Jaworski, and McGinnis (1986) specified three broad types of needs of consumers that determine or impact value.C. Whan Park, Bernard J. Jaworski, and Deborah J. MacInnis, “Strategic Brand Concept Image Management,” Journal of Marketing 50 (1986): 135. Seth, Newman, and Gross (1991)Jagdish N. Seth, Bruce I. Newman, and Barbara L. Gross, Consumption Values and Market Choice: Theory and Applications (Cincinnati, OH: Southwest Publishing, 1991), 77. provided five types of value, as did Woodall (2003), although he did not identify the same five values.Tony Woodall, “Conceptualising ‘Value for the Customer’: An Attributional, Structural and Dispositional Analysis,” Academy of Marketing Science Review 2003, no. 12 (2003), accessed October 7, 2011, www.amsreview.org/articles/woodall12-2003.pdf. To add to the confusion, Heard (1993–94)Ed Heard, “Walking the Talk of Customers Value,” National Productivity Review 11 (1993–94): 21. identified three factors, while Ulaga (2003)Wolfgang Ulaga, “Capturing Value Creation in Business Relationships: A Customer Perspective,” Industrial Marketing Management 32, no. 8 (2003): 677. specified eight categories of value; and Gentile, Spiller, and Noci (2007) mentioned six components of value.Chiara Gentile, Nicola Spiller, and Giuliana Noci, “How to Sustain the Customer Experience: An Overview of Experience Components That Co-Create Value with the Customer,” European Management Journal 25, no. 5 (2007): 395. Smith and Colgate (2007) attempted to place the discussion of customer value in a pragmatic context that might aid practitioners. They identified four types of values and five sources of value. Their purpose was to provide “a foundation for measuring or assessing value creation strategies.”J. Brock Smith and Mark Colgate, “Customer Value Creation: A Practical Framework,” Journal of Marketing Theory and Practice 15, no. 1 (2007): 7. In some of these works, the components or dimensions of value singularly consider the benefits side of the equation, while others incorporate cost dimensions as part of value.

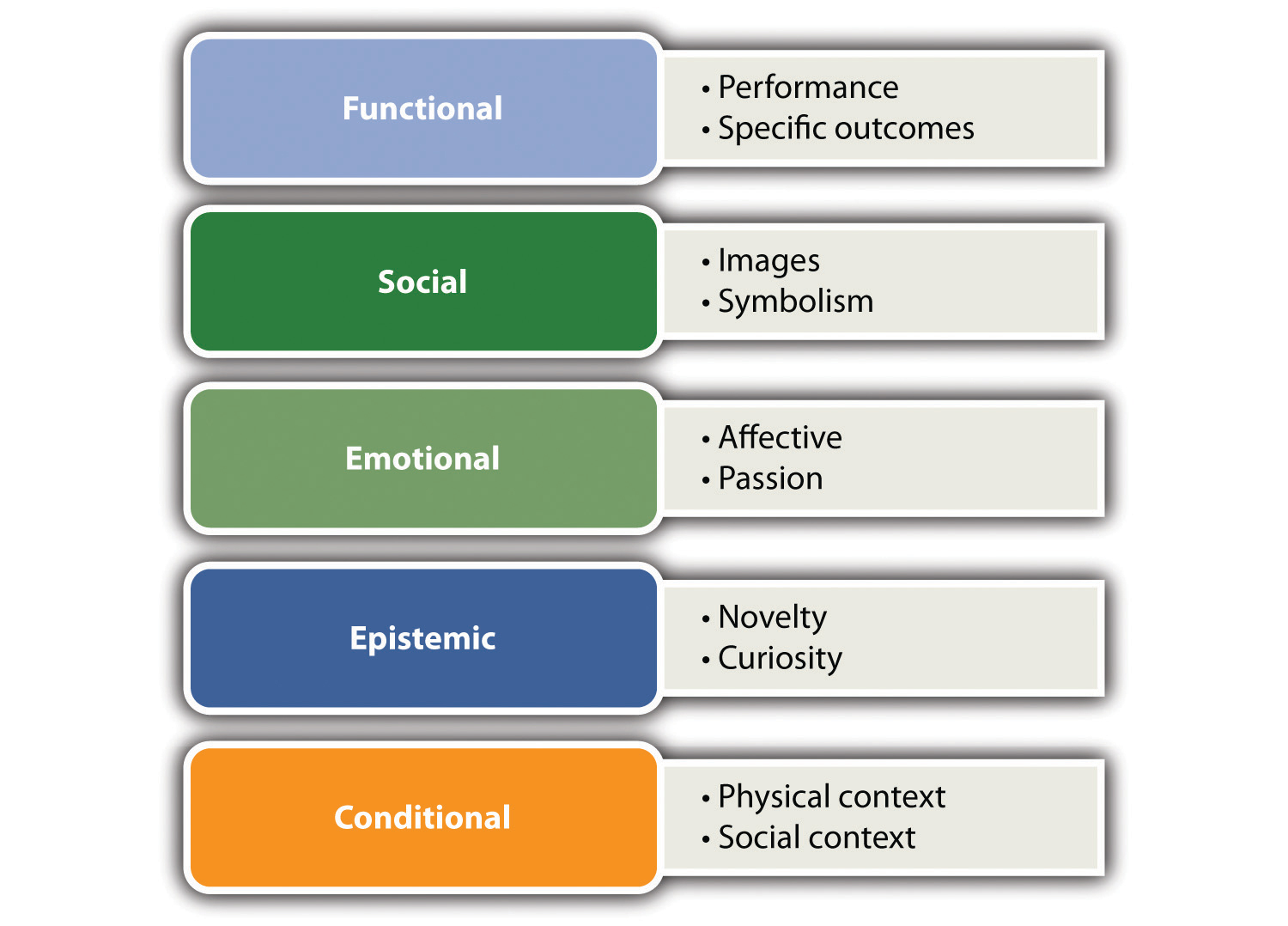

From the standpoint of small businesses, what sense can be made of all this confusion? First, the components of the benefits portion of customer value need to be identified in a way that has significance for small businesses. Second, cost components also need to be identified. Seth, Newman, and Gross’s five types of value provide a solid basis for considering perceived benefits (see Figure 2.2 “Five Types of Value”). Before specifying the five types of value, it is critical to emphasize that a business should not intend to compete on only one type of value. It must consider the mix of values that it will offer its customers. (In discussing these five values, it is important to provide the reader with examples. Most of our examples will relate to small business, but in some cases, good examples will have to be drawn from larger firms because they are better known.)

Figure 2.2 Five Types of Value

The five types of value are as follows:

- Functional value relates to the product’s or the service’s ability to perform its utilitarian purpose. Woodruff (1997) identified that functional value can have several dimensions.Robert B. Woodruff, “Customer Value: The Next Source of Competitive Advantage, Journal of the Academy of Marketing Science 25, no. 2 (1997): 139. One dimension would be performance related. This relates to characteristics that would have some degree of measurability, such as appropriate performance, speed of service, quality, or reliability. A car may be judged on its miles per gallon or the time to go from zero to sixty miles per hour. These concepts can also be seen when evaluating a garage that is performing auto repairs. Customers have an expectation that the repairs will be done correctly, that the car will not have to be brought back for additional work on the same problem, and that the repairs will be done in a reasonable amount of time. Another dimension of functional value might consider the extent to which the product or the service has the correct features or characteristics. In considering the purchase of a laptop computer, customers may compare different models on the basis of weight, battery lifetime, or speed. The notion of features or characteristics can be, at times, quite broad. Features might include aesthetics or an innovation component. Some restaurants will be judged on their ambiance; others may be judged on the creativity of their cuisine. Another dimension of functional value may be related to the final outcomes produced by a business. A hospital might be evaluated by its number of successes in carrying out a particular surgical procedure.

- Social value involves a sense of relationship with other groups by using images or symbols. This may appear to be a rather abstract concept, but it is used by many businesses in many ways. Boutique clothing stores often try to convey a chic or trendy environment so that customers feel that they are on the cutting edge of fashion. Rolex watches try to convey the sense that their owners are members of an economic elite. Restaurants may alter their menus and decorations to reflect a particular ethnic cuisine. Some businesses may wish to be identified with particular causes. Local businesses may support local Little League teams. They may promote fundraising for a particular charity that they support. A business, such as Ben & Jerry’s Ice Cream, may emphasize a commitment to the environment or sustainability.

- Emotional value is derived from the ability to evoke an emotional or an affective response. This can cover a wide range of emotional responses. Insurance companies and security alarm businesses are able to tap into both fear and the need for security to provide value. Some theme parks emphasize the excitement that customers will experience with a range of rides. A restaurant may seek to create a romantic environment for diners. This might entail the presence of music or candlelight. Some businesses try to remind customers of a particular emotional state. Food companies and restaurants may wish to stimulate childhood memories or the comfort associated with a home-cooked meal. Häagen-Dazs is currently producing a line of all-natural ice cream with a limited number of natural flavors. It is designed to appeal to consumers’ sense of nostalgia.“Maturalism,” Trendwatching.com, accessed June 1, 2012, http://trendwatching.com/trends/maturialism/.

- Epistemic value is generated by a sense of novelty or simple fun, which can be derived by inducing curiosity or a desire to learn more about a product or a service. Stew Leonard’s began in the 1920s as a small dairy in Norwalk, Connecticut. Today, it is a $300 million per year enterprise of consisting of four grocery stores. It has been discussed in major management textbooks. These accomplishments are due to the desire to turn grocery shopping into a “fun” experience. Stew Leonard’s uses a petting zoo, animatronic figures, and costumed characters to create a unique shopping environment. They use a different form of layout from other grocery stores. Customers are required to follow a fixed path that takes them through the entire store. Thus customers are exposed to all items in the store. In 1992, they were awarded a Guinness Book world record for generating more sales per square foot than any food store in the United States.“Company Story,” Stew Leonards, accessed October 7, 2011, www.stewleonards.com/html/about.cfm. Another example of a business that employs epistemic value is Rosetta Stone, a company that sells language-learning software. Rosetta Stone emphasizes the ease of learning and the importance of acquiring fluency in another language through its innovative approach.

-

Conditional value is derived from a particular context or a sociocultural setting. Many businesses learn to draw on shared traditions, such as holidays. For the vast majority of Americans, Thanksgiving means eating turkey with the family. Supermarkets and grocery stores recognize this and increase their inventory of turkeys and other foods associated with this period of the year. Holidays become a basis for many retail businesses to tap into conditional value.

Another way businesses may think about conditional value is to introduce a focus on emphasizing or creating a sociocultural context. Business may want to introduce a “tribal” element into their customer base, by using efforts that cause customers to view themselves as a member of a special group. Apple Computer does this quite well. Many owners of Apple computers view themselves as a special breed set apart from other computer users. This sense of special identity helps Apple in the sale of its other electronic consumer products. They reinforce this notion in the design and setup of Apple stores. Harley-Davidson does not just sell motorcycles; it sells a lifestyle. Harley-Davidson also has a lucrative side business selling accessories and apparel. The company supports owner groups around the world. All of this reinforces, among its customers, a sense of shared identity.

It should be readily seen that these five sources of value benefits are not rigorously distinct from each other. A notion of aesthetics might be applied, in different ways, across several of these value benefits. It also should be obvious that no business should plan to compete on the basis of only one source of value benefits. Likewise, it may be impossible for many businesses, particularly start-ups, to attempt to use all five dimensions. Each business, after identifying its customer base, must determine its own mix of these value benefits.

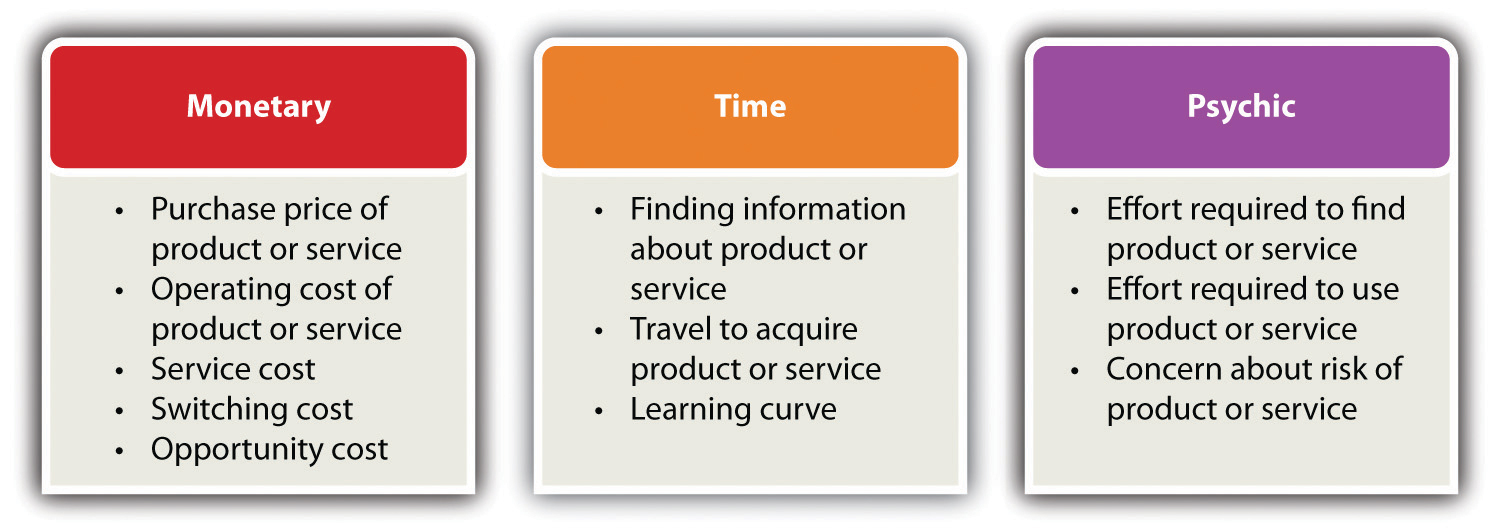

As previously pointed out, the notion of perceived customer value has two components—perceived value benefits and perceived value costs. When examining the cost component, customers need to recognize that it is more than just the cost of purchasing a product or a service. Perceived cost should also be seen having multiple dimensions (see Figure 2.3 “Components of Customer Value”).

Figure 2.3 Components of Customer Value

Perceived costs can be seen as being monetary, time, and psychic. The monetary component of perceived costs should, in turn, be broken down into its constituent elements. Obviously, the first component is the purchase price of the product or the service. Many would mistakenly think that this is the only element to be considered as part of the cost component. They fail to consider several other cost components that are quite often of equal—if not greater—importance to customers. Many customers will consider the operating cost of a product or a service. A television cable company may promote an introductory offer with a very low price for the cable box and its installation. Most customers will consider the monthly fees for cable service rather than just looking at the installation cost. They often use service costs when evaluating the value proposition. Customers have discovered that there are high costs associated with servicing a product. If there are service costs, particularly if they are hidden costs, then customers will find significantly less value from that product or service. Two other costs also need to be considered. Switching cost is associated with moving from one provider to another. In some parts of the country, the cost of heating one’s home with propane gas might be significantly less than using home heating oil on an annualized basis. However, this switch from heating oil to propane would require the homeowner to install a new type of furnace. That cost might deter the homeowner from moving to the cheaper form of energy. Opportunity cost involves selecting among alternative purchases. A customer may be looking at an expensive piece of jewelry that he wishes to buy for his wife. If he buys the jewelry, he may have to forgo the purchase of a new television. The jewelry would then be the opportunity cost for the television; likewise, the television would be the opportunity cost for the piece of jewelry. When considering the cost component of the value equation, businesspeople should view each cost as part of an integrated package to be set forth before customers. More and more car dealerships are trying to win customers by not only lowering the sticker price but also offering low-cost or free maintenance during a significant portion of the lifetime of the vehicle.

These monetary components are what we most often think of when we discuss the term cost, and, of course, they will influence the decision of customers; however, the time component is also vital to the decision-making process. Customers may have to expend time acquiring information about the nature of the product or the service or make comparisons between competing products and services. Time must be expended to acquire the product or the service. This notion of time would be associated with learning where the product or the service could be purchased. It would include time spent traveling to the location where the item would be purchased or the time it takes to have the item delivered to the customer. One also must consider the time that might be required to learn how to use the product or the service. Any product or service with a steep learning curve might deter customers from purchasing it. Firms can provide additional value by reducing the time component. They could simplify access to the product or the service. They may offer a wide number of locations. Easy-to-understand instructions or simplicity in operations may reduce the amount of time that is required to learn how to properly use the product or the service.

The psychic component of cost can be associated with those factors that might induce stress on the customer. There can be stress associated with finding or evaluating products and services. In addition, products or services that are difficult to use or require a long time to learn how to use properly can cause stress on customers. Campbell’s soup introduced a meal product called Souper Combos, which consisted of a sandwich and a cup of soup. At face value, one would think that this would be a successful product. Unfortunately, there were problems with the demands that this product placed on the customer in terms of preparing the meal. The frozen soup took twice as long to microwave as anticipated, and the consumer had to repeatedly insert and remove both the soup and the sandwich from the microwave.Calvin L. Hodock, Why Smart Companies Do Dumb Things(Amherst, NY: Prometheus Books, 2007), 65.

In summary, business owners need to constantly consider how they can enhance the benefits component while reducing the cost components of the value equation. Table 2.1 “Components of Perceived Benefit and Perceived Cost” summarizes the subcomponents of perceived value, the types of firms that emphasize those components, and the activities that might be necessary to either enhance benefits or reduce costs.

Table 2.1 Components of Perceived Benefit and Perceived Cost

| Component | Aspects | Activities to Deliver |

|---|---|---|

| Components of Perceived Benefit | ||

| Functional |

|

|

| Social |

|

|

| Emotional |

|

|

| Epistemic |

|

|

| Conditional |

|

|

| Components of Perceived Cost | ||

| Monetary |

|

|

| Time |

|

|

| Psychic |

|

|

Video Clip 2.2

Creating Customer Value

Creating value is the essence of a start-up. This video reviews the product and value created by a watch with no hands.

Video Clip 2.3

Simple Rules: Three Logics of Value Creation

Three core logics of the value proposition.

Video Clip 2.4

Articulating Your Value Proposition

A video on how to better articulate your value proposition. This is informative but very long (about one hour).

Different Customers—Different Definitions

It is a cliché to say that people are different; nonetheless, it is true to a certain extent. If all people were totally distinct individuals, the notion of customer value might be an interesting intellectual exercise, but it would be absolutely useless from the standpoint of business because it would be impossible to identify a very unique definition of value for every individual. Fortunately, although people are individuals, they often operate as members of groups that share similar traits, insights, and interests. This notion of customers being members of some type of group becomes the basis of the concept known as market segmentation. This involves dividing the market into several portions that are different from each other.“Market Segmentation,” NetMBA Business Knowledge Center, accessed October 7, 2011, www.netmba.com/marketing/market/segmentation. It simply involves recognizing that the market at large is not homogeneous. There can be several dimensions along which a market may be segmented: geography, demographics, psychographics, or purchasing behavior. Geographic segmentation can be done by global or national region, population size or density, or even climate. Demographic segmentation divides a market on factors such as gender, age, income, ethnicity, or occupation. Psychographic segmentation is carried out on dimensions that reflect differences in personality, opinions, values, or lifestyle. Purchasing behavior can be another basis for segmentation. Differences among customers are determined based on a customer’s usage of the product or the service, the frequency of purchases, the average value of purchases, and the status as a customer—major purchaser, first-time user, or infrequent customer. In the business-to-business (B2B) environment, one might want to segment customers on the basis of the type of company.

Market segmentation recognizes that not all people of the same segment are identical; it facilitates a better understanding of the needs and wants of particular customer groups. This comprehension should enable a business to provide greater customer value. There are several reasons why a small business should be concerned with market segmentation. The main reason centers on providing better customer value. This may be the main source of competitive advantage for a small business over its larger rivals. Segmentation may also indicate that a small business should focus on particular subsets of customers. Not all customers are equally attractive. Some customers may be the source of most of the profits of a business, while others may represent a net loss to a business. The requirements for providing value to a first-time buyer may differ significantly from the value notions for long time, valued customer. A failure to recognize differences among customers may lead to significant waste of resources and might even be a threat to the very existence of a firm.

Video Clip 2.5

Tom Peters: The Biggest Underserved Markets

Tom Peters, a self-described “professional loudmouth” who has been compared to Ralph Waldo Emerson, Walt Whitman, Henry David Thoreau, and H. L. (Henry Louis) Mencken, declares war on the worthless rules and absurd organizational barriers that stand in the way of creativity and success. In a totally outrageous, in-your-face presentation, Peters reveals the following: a reimagining of American business; two big markets—underserved and worth trillions; the top qualities of leadership excellence; and why passion, talent, and action must rule business today.

KEY TAKEAWAYS

- Essential to the success of any business is the need to correctly identify customer value.

- Customer value can be seen as the difference between a customer’s perceived benefits and the perceived costs.

- Perceived benefits can be derived from five value sources: functional, social, emotional, epistemic, and conditional.

- Perceived costs can be seen as having three elements: monetary, time, and psychic.

- To better provide value to customers, it may be necessary to segment the market.

- Market segmentation can be done on the basis of demographics, psychographics, or purchasing behavior.

EXERCISES

Frank’s All-American BarBeQue

Robert Rainsford is a twenty-eight-year-old facing a major turning point in his life. He has found himself unemployed for the first time since he was fifteen years old. Robert holds a BS degree in marketing from the University of Rhode Island. After graduation, a firm that specialized in developing web presences for other companies hired him. He worked for that firm for the last seven years in New York City. Robert rose rapidly through the company’s ranks, eventually becoming one of the firm’s vice presidents. Unfortunately, during the last recession, the firm suffered significant losses and engaged in extensive downsizing, so Robert lost his job. He spent months looking for a comparable position, yet even with an excellent résumé, nothing seemed to be on the horizon. Not wanting to exhaust his savings and finding it impossible to maintain a low-cost residence in New York City, he returned to his hometown in Fairfield, Connecticut, a suburban community not too far from the New York state border.

He found a small apartment near his parents. As a stopgap measure, he went back to work with his father, who is the owner of a restaurant—Frank’s All-American BarBeQue. His father, Frank, started the restaurant in 1972. It is a midsize restaurant—with about eighty seats—that Frank has built up into a relatively successful and locally well-known enterprise. The restaurant has been at its present location since the early 1980s. It shares a parking lot with several other stores in the small mall where it is located. The restaurant places an emphasis on featuring the food and had a highly simplified décor, where tables are covered with butcher paper rather than linen tablecloths. Robert’s father has won many awards at regional and national barbecue cook-offs, which is unusual for a business in New England. He has won for both his barbecue food and his sauces. The restaurant has been repeatedly written up in the local and New York papers for the quality of its food and the four special Frank’s All-American BarBeQue sauces. The four sauces correspond to America’s four styles of barbecue—Texan, Memphis, Kansas City, and Carolina. In the last few years, Frank had sold small lots of these sauces in the local supermarket.

As a teenager, Robert, along with his older sister Susan, worked in his father’s restaurant. During summer vacations while attending college, he continued to work in the restaurant. Robert had never anticipated working full-time in the family business, even though he knew his father had hoped that he would do so. By the time he returned to his hometown, his father had accepted that neither Robert nor Susan would be interested in taking over the family business. In fact, Frank had started to think about selling the business and retiring. However, Robert concluded that his situation called for what he saw as desperate measures.

Initially, Robert thought his employment at his father’s business was a temporary measure while he continued his job search. Interestingly, within the first few weeks he returned to the business, he felt that he could bring his expertise in marketing—particularly his web marketing focus—to his father’s business. Robert became very enthusiastic about the possibility of fully participating in the family business. He thought about either expanding the size of the restaurant, adding a takeout option, or creating other locations outside his hometown. Robert looked at the possibility of securing a much larger site within his hometown to expand the restaurant’s operations. He began to scout surrounding communities for possible locations. He also began to map out a program to effectively use the web to market Frank’s All-American BarBeQue sauce and, in fact, to build it up to a whole new level of operational sophistication in marketing.

Robert recognized that the restaurant was as much of a child to his father as he and his sister were. He knew that if he were to approach his father with his ideas concerning expanding Frank’s All-American BarBeQue, he would have to think very carefully about the options and proposals he would present to his father. Frank’s All-American BarBeQue was one of many restaurants in Fairfield, but it is the only one that specializes in barbecue. Given the turnover in restaurants, it was amazing that Frank had been able to not only survive but also prosper. Robert recognized that his father was obviously doing something right. As a teenager, he would always hear his father saying the restaurant’s success was based on “giving people great simple food at a reasonable price in a place where they feel comfortable.” He wanted to make sure that the proposals he would present to his father would not destroy Frank’s recipe for success.

- Discuss how Robert should explicitly consider the customer value currently offered by Frank’s All-American BarBeQue. In your discussion, comment on the five value benefits and the perceived costs.

- Robert has several possible options for expanding his father’s business—find a larger location in Fairfield, add a takeout option, open more restaurants in surrounding communities, incorporate web marketing concepts, and expand the sales of sauces. Review each in terms of value benefits.

- What would be the costs associated with those options?